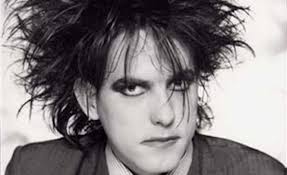

Dark, demented, tormented, torrid and tetchy? Oh, I don’t think so. The Cure’s Robert Smith might have gained something of a reputation in his 40-year-plus tenure as the leader of one of the most enduring of alternative post-punk bands, but these days you will find him basking in the glow of sun shining throughout The Cure’s Indian summer. Yes, Smith was once perceived as the epitome (and, indeed, the spokesperson) of teenage sulking, but he now has in his 60s what he didn’t have at 16: perspective, insight, history, intellectual depth, a sense of irony.

“Good music – emotionally connecting music, in particular – transcends a lot of the traditional pop music age barriers, and if you’re more into image and being of the zeitgeist, so to speak, then you’re much more concerned about being young, and quite rightly in my opinion. Every generation needs its own bands and their own spokespeople. I wouldn’t dream that what I write or what we play represents a younger generation, but I think emotionally it connects. What The Cure has, I hope, is something of a timeless quality to it. It isn’t really to do with how old we are.

“Having said that, yes, of course I’m aware of us growing older, and it feels very strange because in my head I don’t feel as old as I am. Certainly, when I’m singing there are times when I come to the end of a song and think, good grief, it’s been a long time since I wrote that one!”

Formed in 1976 in West Sussex, Smith’s early teenage music tastes were steered from the likes of Eric Clapton and Rory Gallagher (“he was the very first music act I saw. I went on my own to the Brighton Dome in 1974, and I was completely entranced. A phenomenally good guitarist…”) to the year-zero moods and modes of punk rock. The Cure’s 1979 debut album, Three Imaginary Boys, set out the kind of stall that should by rights have buckled, yet within a few years the band morphed from trembling, morose teenagers into a fixed unit that effectively created their own genre of pop music.

By the mid-80s, albums such as Faith (1981), Pornography (1982), The Top (1985) and The Head on the Door (1985) brought The Cure moderate worldwide fame, not only as a band that defined (unwittingly or not) a sombre, often nihilistic worldview (“it doesn’t matter if we all die” sings Smith on Pornography) but also one that could conjure up a tune you could whistle on your way to work. By the early ’90s, however – with the band even more successful via the global smash album, Wish, and hit singles such as Friday I’m in Love – moderate fame had turned into massive adulation. Cue enormo-domes. Cue a miserable two years. Cue meltdown.

“Yes, that’s when I took a break for a few years,” recalls Smith wistfully. “Wish was number one in pretty much every chart in the world, and we were playing giant football stadia. Our success had escalated to the point where I just couldn’t cope with it any more, and so I had my own version of a breakdown.”

The way Smith tells it (and he relates it, by the way, with eloquence, reflection and humour), he had become a hugely successful and very recognizable celebrity, who had no idea how it had happened. “The band became enormous – back then, we were on an upwards trajectory, and we were presented with this idea that we could become the biggest group in the world and stay there. What that requires is an ego-driven desire that I just didn’t – and don’t – have. But how The Cure got to that point was almost farcical.”

Imagine a band trying desperately not to become popular, yet suddenly being elevated to the status of an anti-everything pop act that could sell out massive venues. It was bizarre, remembers Smith, who readily admits that there was no one around them – or in the band, for that matter – with a plan. “Other bands may have had a shadowy manager – in some cases not so shadowy – that pulls the strings and makes things happen,” he elucidates. “We had none of that. We were just careering around, doing whatever we wanted and however we wanted, and somehow it all just seemed to fall into place.”

Once they reached that level, Smith says, they were then surrounded by hundreds of people making vast amounts of money out of them. “Their one goal is to get you to continue on this upward path, and so I just had to escape from it. I walked away, other band members left, and for a few years the group just ceased to be. I’d had enough. When we came back we started down the ladder a bit, and that suited us perfectly. Now, it’s the experience of playing, and how well we do it, not where The Cure might stand in the pantheon of rock music. History will write our name, however large or not, and that’s totally beyond my control.”

Control, it seems, is crucial for Smith, as is loyalty. Issues of each have filtered throughout Smith’s life and The Cure’s career for decades, yet there’s an apparently casual disconnect between the two. He recalls firing people on will-o-the-wisp whims (“I’m sure I was looked upon as a nightmare”) but admits that perhaps the main constant in his life is his wife, Mary, to whom he has been married for over 30 years (they met when Smith was 14, and in a super aah-shucks scenario, whenever Smith is on tour outside the UK she keeps his hours so that they can phone each other routinely).

Another aspect that Smith holds onto for dear life is the emotional connections to his music, “When I’m on stage and sing a song from the early days, I can honestly still identify with what I was thinking, what I was feeling at the time I wrote it. A lot of what is dismissively referred to as ‘teenage angst’ has actually never gone away for me. In fact, I’ve never been able to get rid of that, never found anything to replace it.”

Does middle-aged angst ever enter into things? “Ha! Well, angst is angst, isn’t it? The most difficult thing about getting old is avoiding becoming too cynical. As the years pass you get to know too much, so resisting the urge to give up on everything and everyone is my struggle these days.”

Angst and encroaching cynicism aside, Smith seems to be enjoying the kind of rude health in both life and music that many of his peers and contemporaries have been missing for some years. He is at pains to point out that The Cure – meaning, efffectively, himself, as members have come and gone through the decades – still cling to old-school punk tenets such as doing things for the right reasons.

“Well, here’s the thing,” he posits. “I despise people who do what I do and who pretend they’re somehow not part of the machine. You are, you just are, and you can’t possibly avoid it. We were fortunate back in the day in that the trajectory of The Cure was always up. I always knew that was a trump card – I could often make an outrageous demand and call people’s bluff. Doing things in the way I wanted to do them has always been more important to me than doing it a different way, because I always wanted to fail – or succeed – on my own terms.”

The Cure’s modus operandi, such as it is, says Smith, is quite simple: just do it how you want to do it. “If it goes right, everyone is astonished, and so you do it some more. There is no great plan beyond having self-belief, albeit sometimes an incredibly arrogant self-belief.”

What if it had all gone wrong, though? What if darkness, dementia, torment, wretched bad temper and ginormous commercial success hadn’t been generated? Smith isn’t interested in theoretical questions, though, and he politely, blithely swats these away.

“Oh, I’d be doing something else, no doubt, but at least I would look back and feel proud that I’d failed on my terms. If I’d failed on somebody else’s terms I can’t imagine how bitter I’d be as an older man.”

(This updated feature was first published in The Ticket/Irish Times, August 2012.)